3 Method

The research complied with all relevant ethical regulations and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Johns Hopkins University. In two experiments, online participants played online versions of two information-seeking games. In Battleship (Exp. 1), 500 English-speaking players (recruited from Prolific.com) were presented with a 5x5 grid of yellow squares, and attempted to reveal one size-3 submarine and two size-2 patrol boats with as few guesses as possible. In our version of the game, ships could only touch corner-to-corner, but not side-to-side (this was explained to participants before playing), and participants were not notified once they had sunk a ship (only whether their guess was a hit or a miss). In Hangman, N=501 English-speaking players attempted to reveal a hidden word, name or number (hereafter referred to broadly as “word’) with as few letter-guesses as possible, based on word length and category (a famous person, number, fruit, US state, or body part). To ensure familiarity with US states, Hangman participants were all US-based.

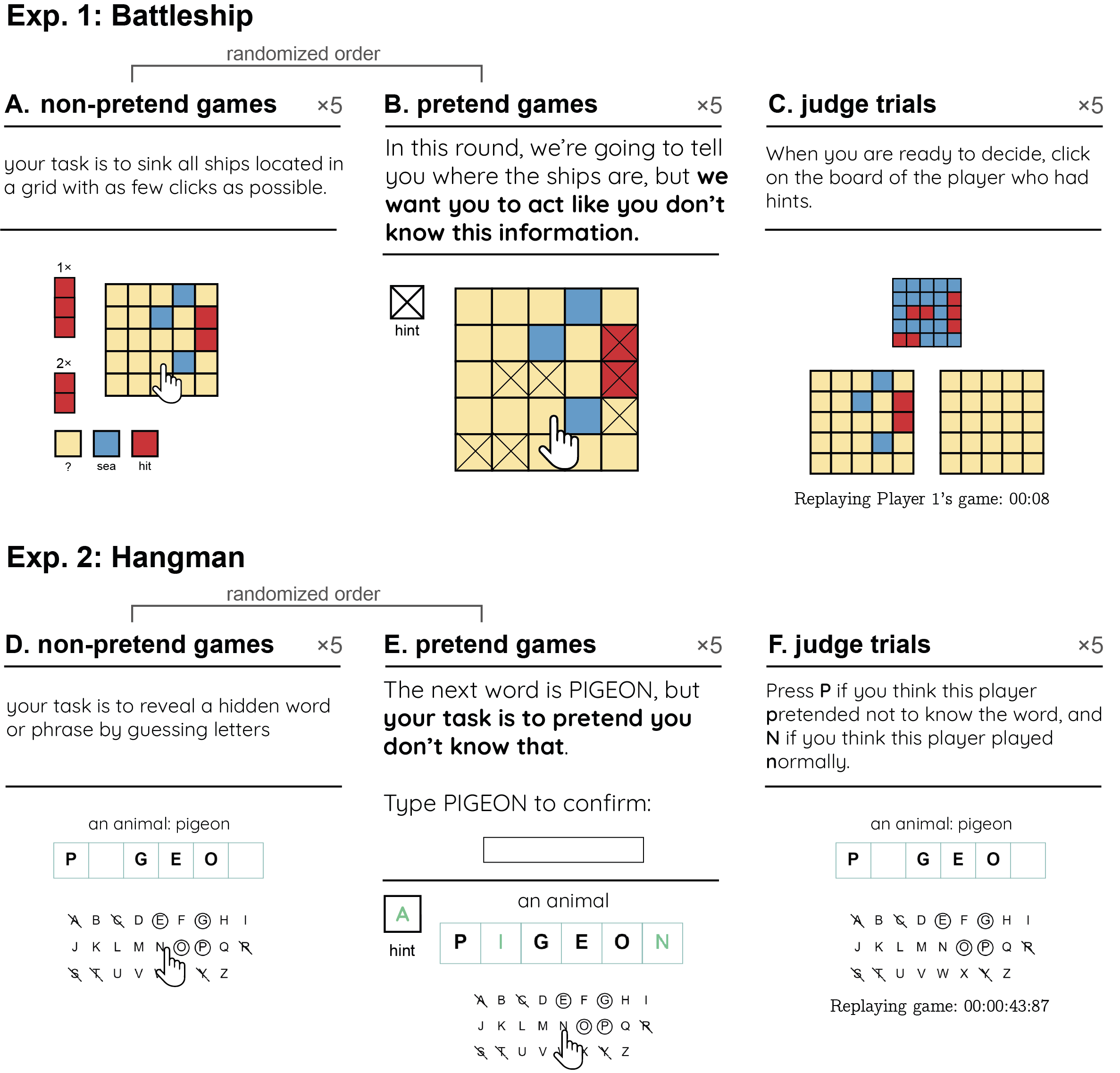

Both games traditionally start in a state of ignorance, with a player’s goal being to reveal an unknown world state (ship locations in Battleship, a hidden word in Hangman) in as few steps (cell or letter selections) as possible. Critically, in addition to playing five standard games, players in our experiments also completed five ‘pretend’ games in which the solution to the game was known to them from the start and remained visible on the screen throughout the entire game (pretend-Battleship ship locations were marked with a cross, pretend-Hangman words were presented visually and had to be typed by players before the game, to ensure encoding; see Fig. 3.1). In these games, players’ task was to behave as if they were playing for real – i.e. to play as though they did not have this information.

Throughout the game, participants accrued points that were later converted to a monetary bonus. In non-pretend games, participants received points for revealing the ships, or the target word, with as few guesses as possible. In pretend games, participants were given different instructions:

“In this round, we’re going to tell you where the ships are, but we want you to act like you don’t know this information. We’ve marked the ships’ locations with a cross, so you’ll know where they are the whole time; but your job is to play the game as if these hints aren’t there. To see how good you are at this, we’re going to compare your games to the games of people who actually had no hints, and see how similar they are. We will measure where and when you clicked; if your clicks look similar to people who played like normal (trying to reveal all ships with as few clicks as possible, but without any hints), you’ll get bonus points. But if your games look different, you won’t get these bonus points. Your number of clicks in this part will not affect your bonus. Only your ability to play like you had no hints.”

And in Hangman:

“In this round, we’re going to tell you the word in advance, but we want you to act like you don’t know this information. To see how good you are at this, we’re going to compare your games to the games of people who played normally, without knowing what the word was, and see how similar they are. We will measure which letters you click and the timing of your guesses; if your clicks look similar to people who played like normal (trying to reveal the word with as few guesses as possible, but without any hints), you’ll get bonus points. But if your games look different, you won’t get these bonus points. Your number of clicks in this part will not affect your bonus. Only your ability to play like you didn’t see the word in advance.”

We intentionally included no reference to an observer in these instructions, to have participants focusing on simulating their own behaviour rather than simulating how their behaviour would be perceived by another person. In reality, participants’ games were presented to other participants, and they received bonus points if they tricked these other participants into believing they did not have hints.

Players played pretend and standard games in separate blocks that were presented in random order after a first ‘practice’ game. In principle, participants could learn about their own behaviour from this practice game. To minimize such learning effects, we distinguished practice games from the main experimental blocks, using a smaller 4x4 grid with only two size-2 ships in Battleship, and a word category (animals) that was not used in the main experiment in Hangman. Each experimental block was followed by a half-game, where players were instructed to complete the game from a half-finished state. Finally, players were presented with replays of the games of previous players, and judged which were standard and which were pretend games. We measured players’ capacity to simulate a counterfactual state of ignorance by comparing patterns of decisions and decision times in pretend and non-pretend games. Our full pre-registered results are available online together with the report-generating code. Unless otherwise specified, all reported findings similarly hold when analysing only the first condition performed by each subject in a between-subject analysis, thereby ensuring that findings are not driven by learning effects1. Readers are invited to try demos of the experiments.

Figure 3.1: Experimental Design in Exp. 1 (upper panel) and 2 (lower panel). In non-pretend games, players revealed ships by guessing cells in a grid (A) or revealed a word by guessing letters (D). In pretend games, we marked ship locations with a cross (B) and revealed the target word from the start (E), but asked players to play as if they didn’t have this information. Lastly, players watched replays of the games of previous players and guessed which were pretend games (C and F).

In both experiments, the order of pretend and non-pretend blocks was counterbalanced between participants. We observed no significant interaction between the strength of any of our effects (i.e., differences between pretend and non-pretend conditions) and part of the experiment (i.e., first versus second). For full details see Supplementary Materials.↩︎